The "I-You" Relation as a Being and a Becoming

a condition of complete simplicity, of non-preferential intimacy

For Martin Buber’s I and Thou, our beginning was relation. Relation is inherently prior to language and any system of thought we’ve conceived of. Even our initial experiences of the world as newborns reflect this desire for relation:

“The innateness of the longing for relation is apparent even in the earliest and dimmest stage. Before any particulars can be perceived, dull glances push into the unclear space toward the indefinite; and at times when there is obviously no desire for nourishment, soft projections of the hands reach, aimlessly to all appearances, into the empty air toward the indefinite. Let anyone call this animalic: that does not help our comprehension. For precisely these glances will eventually, after many trials, come to rest upon a red wallpaper arabesque and not leave it until the soul of red has opened up to them. Precisely this motion will gain its sensuous form and definiteness in contact with a shaggy toy bear and eventually apprehend lovingly and unforgettably a complete body: in both cases not experience of an object but coming to grips with a living, active being that confronts us, if only in our "imagination." (But this "imagination" is by no means a form of "panpsychism"; it is the drive to turn everything into a You, the drive to pan-relation - and where it does not find a living, active being that confronts it but only an image or symbol of that, it supplies the living activity from its own fullness.)”

(I and Thou, 78)

For Buber, there are two ways of being in the world: I-It and I-You.

I-It is the ontological mode through which we mainly experience the world. It is fundamentally mediated by normative procedures of thinking, much of which becomes unthinking to the extent it becomes internalized and unthinkingly acted upon. Beings no longer recognize other beings as entire beings, but as an essentialized set of particulars and on occasion, they miscategorize that set as a “You”. In I-It, the It becomes an object for I, and the I becomes a mere observer making external and internal analyses and coming to conclusions. The German word for object Buber uses here is “Gegenstand”, which literally means “that which stands against”. The I and the It have determinative boundaries; they are perceived as excluding one another. Particularly in the way we deal with sentient beings, giving too much credence to the caricatures we form of others allows for certain behaviors and actions to go unexamined. Martin Luther King Jr. said this in regard to segregation as a form of I-It:

“Segregation substitutes an "I-It" relationship for the "I -Thou" relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. So segregation is not only politically, economically, and sociologically unsound, but it is morally wrong and sinful.” (Letter from a Birmingham Jail, 3.)

And as the I-It mode gets pushed by the powerful into the zeitgeist for their benefit, the I in the I-It is at risk of becoming an It themselves. When we essentialize ourselves as a means toward some end that gives us currency in certain artificial value systems (such as pretending to be other than we are or presenting ourselves in a certain way and value judging certain particulars positively and negatively), we reduce ourselves to an objective means rather than an end in ourselves. Of course, we need to operate in the I-It mode in order to survive (as it is the normative way of being in the world), but it becomes a problem when we overextend and totalize the conclusions from the I-It. That objectification of oneself can become a hardened shell, in which one may retreat into complacent comfort in the midst of being confronted by the You, safe from risking any part of their being.

“Shattered in history / Shattered in paint / Oh, and the lengths that I'd / Stay up late / But brought to my space / The wonderful things I've learned to waste / I shoulda known / That I shouldn't hide / To compromise and to covet / All what's inside”

(Faith, Bon Iver)

I-You is the ontological mode in which we encounter other beings with our entire being. A momentary approach back toward the original state of being: again, undifferentiated relation.

“-What, then, does one experience of the You?

-Nothing at all. For one does not experience it.

-What, then, does one know of the You?

-Only everything. For one no longer knows particulars.”

(I and Thou, 61)

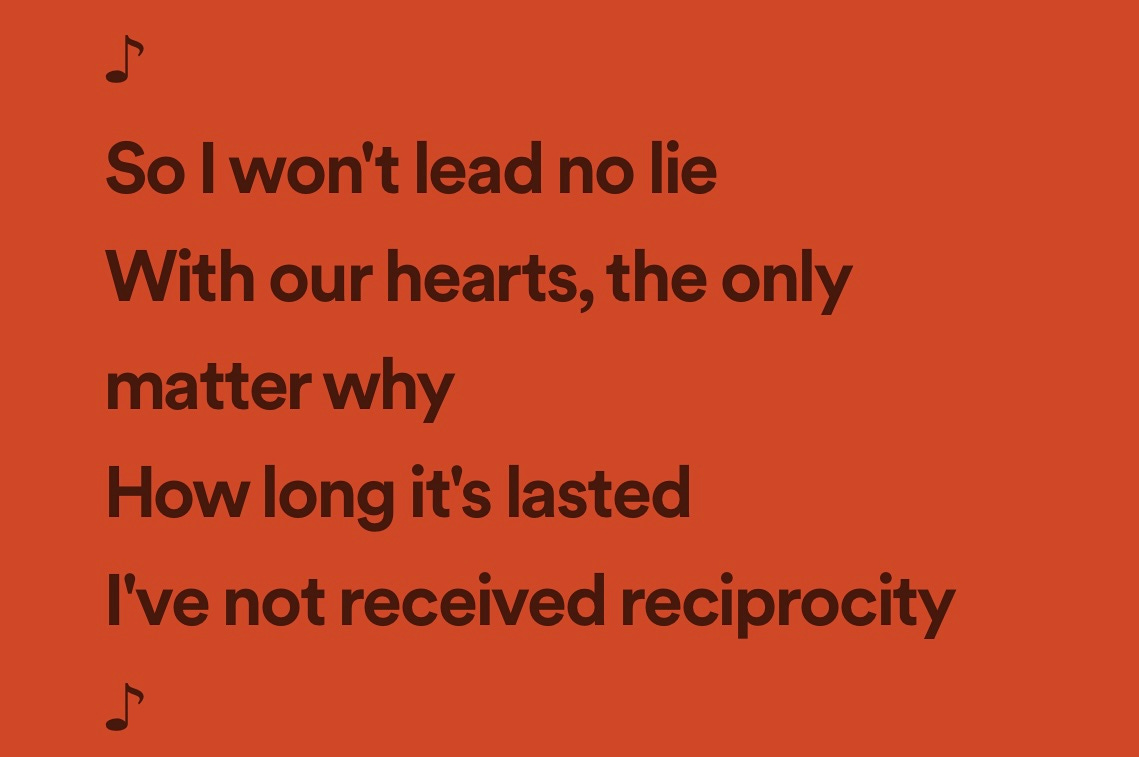

The I-You is an event of non-preferential intimacy. The original German for the English title, I and Thou, is “Ich und Du”, where Du and Thou are the informal versions of the second person singular as opposed to the formal. The I-You relation is stripped of formalities, it is encountered as not mediated by any inherited pre-existing structures. Yet it is not rid of all forms of the “I-It”. We still speak in language, and experience with distinctions with the You. However, the man-made structures that mediate “I-It” get pushed into the background as the “I-You” encounter takes center stage in the event of direct relation. We almost become unconscious of the structures we use as we direct full consciousness to the You. The event is also a risk, as we put forth our own being in its entirety and become vulnerable in the hopes of encountering a You in return. As Buber says, relation is reciprocity, a “condition of complete simplicity (costing not less than everything)” (Little Gidding, Four Quartets – T.S. Eliot). In the I-You encounter, the I and the You exist in a kind of osmotic equilibrium, the membranes of the You become porous and temporarily live in mutual exchange with one another before separating and returning to the world of I-It. But it is faith in the spontaneous emergence of the You that allows one to be open to an encounter with the You, because the You isn’t sought out, it is encountered in a state of active passivity and receptivity.

Am I dependent in what I’m defending? / And do we get to hold what faith provides? / Fold your hands into mine / I did my believing / Seeing every time

(Faith, Bon Iver)

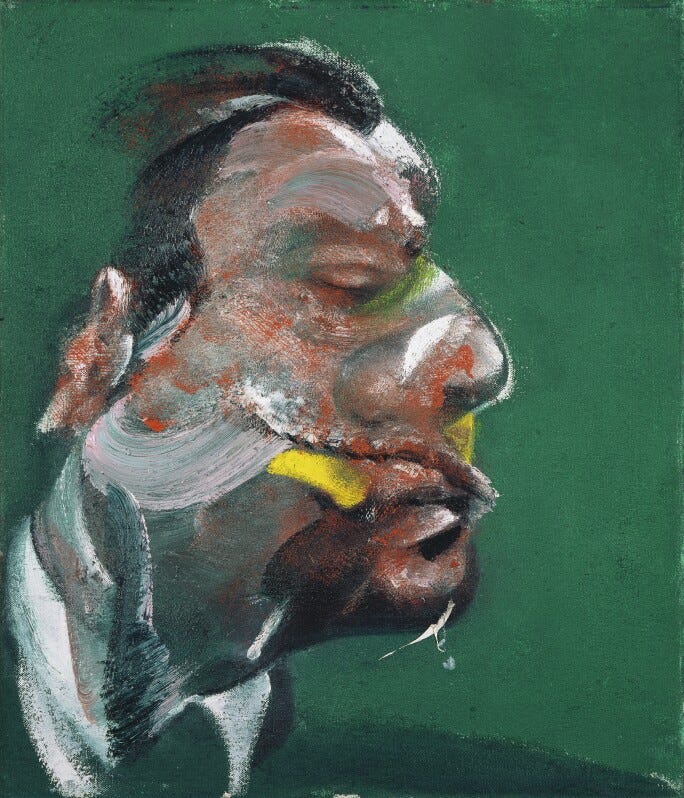

However, can the You be encountered in non-sentient entities? Ones typically perceived as Its? Buber does say we can have an I-You relation with a tree, for example. But to pick out a richer example, Buber’s background in art history clearly signals art as being a rich realm to encounter the You in non-sentient entities.

Art can exist as an expression of the You in the forms of It. However, any art, The You expresses itself by simultaneously dying in its own Youness and birthing into the world of It. It is the sacrifice of the You, its word becoming flesh, if you will, shedding its infinite possibility and becoming reified and actualized in the world. But the You does this in the faith that its multiplicity will be reanimated and abundant in the Is that encounter it in its It form and have an I-You encounter with it. But other than through art, how might we open ourselves up to the possibility to an encounter with the You?

Here I will add my own thoughts onto Buber’s: what if the encounter with the You isn’t just with another being, but also encountering the You as if it were a becoming? Representational thinking is directing the meaning of objects or events toward some higher order unifying concept. This way of thinking belongs to the world of It in two ways. Firstly, it is selective in extracting certain particulars and declaring that to be something’s essence. Secondly, freezes the You in its organic, perpetually pulsating movement, framing it in a static image. Consider the event in which one speaks to a loved one and realizes they weren’t who they thought they were. The language of “You’ve changed” implies some previously held, fixed notion of a person that is in reality, always growing and changing. One must dissolve their I-It notions of the You in order to allow it to move as such. Not that It notions are inherently bad, we still need to be able to have a consistent way of identifying a person, of course. But when taken too far, we restrict the You in itself.

This for my sister / That for my maple

It's not going the road I'd known as a child of God

Nor to become stable / (So what if I lose? I’m satisfied)

(Faith, Bon Iver)

The I encountering the You as a becoming might also recognize the You as horizonal, one recognizes that they are both in the whole presence of the You as being as well as acknowledging and creating space for the unknown. Perhaps recognizing the You in itself is seeing the known as well as a holding space for the unknown as I am confronted by You. An acknowledgement of the limits of vision as well as a love for the mystery of the You’s unknown terrains of past and future. The heart is receptive as well as elastic, rather than closed off and rigid. Instead of remaining static and demanding the You to conform or halt, one encounters the You, recognizes their movement, moves into rhythm with it, a momentary dance with the You.

It is in encounter with the You that we nurture our primordial and innate desire for relation. If that is, like Buber says, we are fundamentally relational. We are human because we search for and are sustained by relation with the You. Under Buber’s framework, I think we become less human when we become over reliant on the I-It mode of being. We become more human when we return toward and move in relation with the You and its movements.

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything)

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.”

(Little Gidding, Four Quartets - T.S. Eliot)